[proto-ecs] Introduction

Luis Diaz / January 2024 (2537 Words, 15 Minutes)

In this article, I present the core concepts and motivations behind proto-ecs, a project I’m developing with a good friend of mine to learn Game Engine programming. If you want to learn more about the context of this project, please visit this index post where I talk about it.

Object models

An object model (and specifically the runtime object model) is the layer of the engine that manages entities in a game and serves as an interface to internal engine systems. Managing an entity requires a lot of services, but the most relevant for our purposes right now are:

- Lifetime: Definition, creation, destruction, initialization, updating…

- Hierarchy: Relationships with other entities, particularly spatial relationships, and how that affects updates.

- Access to engine services: Assets, physics, rendering, audio…

There are many ways in which this can be implemented, each with its benefits and drawbacks. Let’s look at some popular examples we have out there:

- Plain old OOP: You would just create custom classes for each entity in a game, inheriting from a class hierarchy to reuse code and implementing the new behavior in a specialized class. This is the trivial way of implementing an object model and probably the basis for all other models.

- Entity-Component model: In this model, you have an entity that manages initialization, update, and destruction logic, and components. Components are objects that implement the actual behavior. This is an iteration over the plain old OOP model where you favor composition over inheritance. In this model, entities are turned into component collections. You can do this more or less data-driven:

- In Unreal with C++, for example, you would create a specialization of an Actor class (the entity) where you would define components as class members. This actor class would define more properties, initialization, and overall wiring logic between components, while components implement the actual behavior. In this style, the behavior is implemented both in components and the entity.

- On the other hand, in Unity, we would almost always inherit from

MonoBehaviorto implement a component and handle wiring logic between components in the component itself. Entities are created on the editor by attaching components to a GameObject, and entity types are created by spawning instances of prefabs. In this design, the behavior is implemented by components, and entities are a collection of components: their behavior is defined by the components they contain.

- Entity Component Systems: In this model, things are way different than the previous ones. Components are just data, storage where the state is saved for the systems to iterate on. Actual behavior is implemented in systems, functions that don’t store any local state and operate over each entity that matches a signature. The signature is a list of required components for that entity. Entities are usually not proper objects but an abstraction of an object represented as an ID, so an entity is an ID related to components, and those components are updated by systems.

There are more object models and each of them can be implemented in many ways, but these are the most relevant for our task at hand. If you want to learn more about object models, check:

- Game Engine Architecture, Chapter 16: Runtime Gameplay Foundation Systems

- This video from Bobby Angelov shows a lot of what we are about to talk about anyway.

Reference Hell

Every object model has its benefits and problems. The plain OOP and entity-component models are easier to understand since they are similar to how we usually think about the world, but they inherit all the problems we already know from OOP (the death diamond, hard-to-understand hierarchies, careful state manipulation in specialized classes, and so on). ECS is highly efficient but hard to reason and not all gameplay code benefits in the same way from its strict design.

We can talk at length about problems and solutions in object models but the core problem we will be focusing on is the reference hell.

Commonly, a component of our game might need to interact with other components. They can have dependencies, even mutual dependencies, they can manipulate the same data, have execution order dependencies, and be referenced by any other thing in our game. All of this makes it hard to parallelize gameplay code since there’s no easy way to know when two processes depend on the same data. This is especially true for gameplay code where we handle interactions between many entities and even between components of the same entity. This is the reference hell problem because usually to do this you require a lot of references to components and entities stored everywhere.

Since there’s usually a spider web of dependencies and references between many components in a game, it’s hard to parallelize gameplay code without putting locks everywhere. This is even worse when we consider that many components don’t require interactions with other elements, they just update the internal state. In those cases, we would like to use data parallelism but we can’t because you never know when that component is required for other processes that might run in parallel, introducing data races.

ECSs offer a good solution for this problem, you don’t store pointers to anything, you ask explicitly what you need. We shift from implicit dependencies to explicit dependencies. Notice that the object-component models create these implicit dependencies the moment we call GetComponent and GetEntity operations, while an ECS defines explicit dependencies the moment you create a system, by its type signature. Since you explicitly know which components you need at any time, you know which processes can run in parallel, and this is something that can be done automatically without any programmer intervention.

This difference in the way a component defines its dependencies is the origin of the reference hell problem.

proto-ecs

The following design is heavily inspired by this video from Bobby Angelov. The core idea is to reach a middle point between the object component model and the ECS model. Our main goals are:

- No implicit dependencies: Since most of the problem comes from implicit dependency operations, the whole point of this system is to get rid of them, and use explicit dependencies instead. Entities can have their update logic, but they can’t operate directly over other entities.

- Trivial parallelization: There should be minimal user input to achieve parallelization whenever possible. There should be no need for locks and complex synchronization mechanisms in gameplay code, only in engine code.

Components

Our engine has the following components:

- Datagroups: As their name implies, they are data storage. They can implement logic to encourage encapsulation, just not update logic. Datagroups would be considered components in a standard ECS. Datagroups can’t store references to other datagroups, entities, or global systems

- Local Systems: Functions that operate over a single entity. They can specify which datagroups to expect from the entities they operate on, and implement update logic. They are functions because they are stateless, their state is represented as the current values of datagroups in the entities they operate in. Local Systems don’t operate in more than one entity at a time. Unlike traditional ECSs, local systems are opt-in and entities should specify which local systems they want to execute. A local system can have as many functions as stages, more on that later.

- Global Systems: These are singleton objects that move data between entities, and implement inter-entity update logic. They specify which datagroups the entities should provide, they can have internal state and are opt-in: entities specify if they want to be part of some global system.

- Stages: A stage represents a segment of a frame step. It runs all the update functions and book-keeping operations that might be needed after they are called. There are many stages so that update functions have plenty of room to specify execution order concerning other systems. Each stage calls the update function for that stage in all entities and global systems in the right order.

- Entities: Unlike traditional ECSs, entities are actual objects instead of IDs, they store the entity state represented as a list of datagroups and keep track of which local systems are required for that entity. Entities are created in a data-driven manner, they are not objects where the datagroups are a class member, an entity is defined by a collection of datagroups and systems.

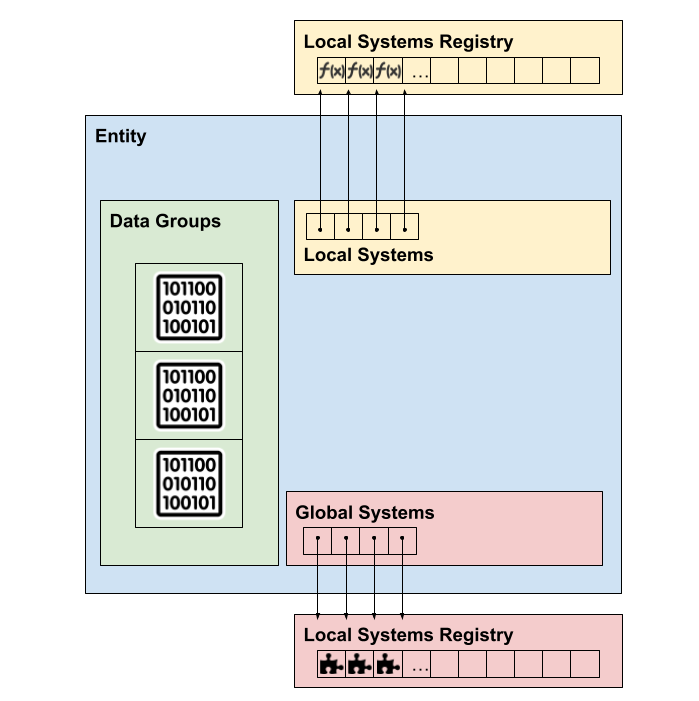

|

|---|

| This Diagram illustrates what an entity looks like. They store the actual datagroups they need, and they have pointers to the local systems they require and the global systems they are subscribed to. Both the local and global system registries are just objects that hold the entire list of global and local systems defined throughout the project. |

Workflow

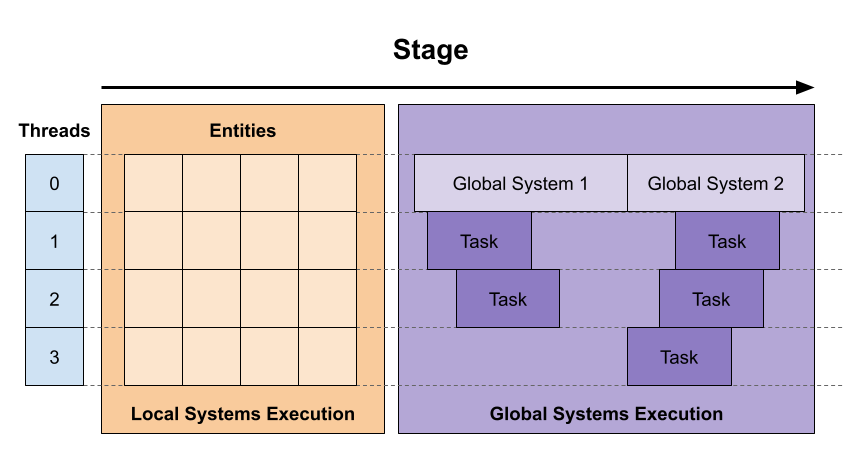

The idea is that since local systems can only operate one entity at a time without access to anything else in the engine, they can be executed in parallel without any problem, and we can employ data parallelism. All entities in the engine are sent to a thread, and their local systems are executed in that thread. On the other hand, global systems affect more than one entity by definition, so they are harder to parallelize. In this case, we use task parallelism, global systems are executed in a single-threaded manner by default, but they can start tasks to run in other threads. The following image shows how this works:

|

|---|

| This is what happens in every stage of execution. Each entity is assigned a thread, and all local systems in that entity are executed. After all local systems finish their update, then global systems call their corresponding update function. All global systems are called in the same thread one after the other, but they can use task parallelism to request tasks to be executed in other threads. However, the consistency of parallel tasks is the responsibility of the programmer. |

Note 📝: To prevent users from modifying the state of other entities in the engine during a local system execution, all local systems are given their required datagroups as arguments. This is similar to how in an ECS a system requires specific components by its type signature. Another way to say this is that local systems use a push model instead of a pull model, so that they can only be given what they request in advance, and the things they can request are limited.

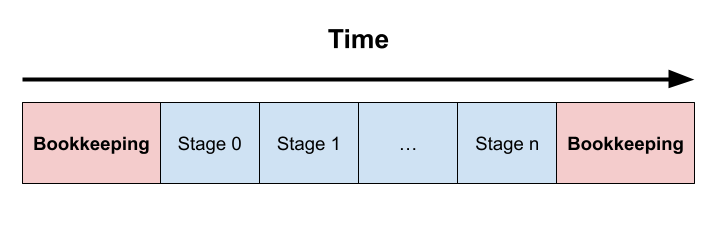

There are many stages in a frame, they represent things like Update, PostPhysics, FrameStart, FrameEnd. There are enough stages to solve most execution order problems. A typical frame looks like this:

|

|---|

| Every frame, each stage is executed sequentially following the structure we talked about earlier. Before and after all stages are executed there’s a bookkeeping step where many requests to the engine are fulfilled, like entity destruction operations for example. They are called bookkeeping operations because they usually involve updating internal engine structures that are used to manage entities and systems. |

The game state is really simple, it’s just:

- A list of entities: The entire array of currently active entities.

- The list of global systems: A list with the state of all loaded global systems. Global system functions are then called with their stored state and a subset of registered entities from the entity list.

- Internal structures: There are a lot of control structures used internally to optimize many engine tasks.

Hierarchies

A problem we haven’t addressed so far is how we work with hierarchies, specifically spatial hierarchies. Since entities can’t store references to other entities, we couldn’t model spatial hierarchies. Even if we could, with the model we have defined so far it would be impossible to keep a consistent update order between entities and their local systems. The biggest issue here starts with transforms; when you modify a transform, you also have to update all children of the modified entity to update their parent transform, but since they are all executing at the same time, you could run into race conditions.

To solve this issue we define a special engine-provided Transform Datagroup that is the only datagroup allowed to have references to other entities, and those references are not public to the user. There are no GetParent operations. The transform also holds the local transformation matrix for this entity and its parent’s transformation matrix. When the parent changes its transform matrix, the Transform Datagroup will automatically update the transform for each of its children.

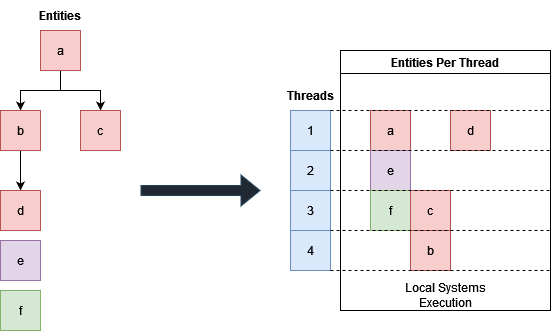

When an entity has a spatial relationship to other entities, the update order is restricted in a way so that the child entity is always updated after the parent entity:

|

|---|

| Entities with spatial dependencies are scheduled to run after their parent, while entities without spatial relationships can run in any thread. In this example, e, a, and f run as soon as possible. When a is finished, b and c can start in any thread, even at the same time, since they don’t care about each other’s execution. And finally, d has to wait until b is finished. |

The idea here is that all entities will be updated after their parents. Note that since spatial relationships change the execution order within a frame, we don’t allow reparenting operations to occur before the frame ended. All reparenting operations are enqueued on request and delivered after the frame has finished.

Execution order

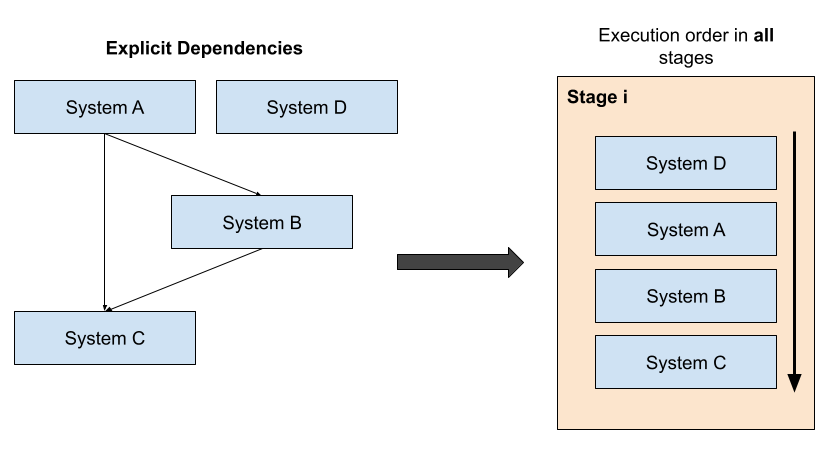

Each system, global or local, provides a set of update functions to be called once per stage. The execution order between functions within the same stage can be specified. When defining a system, you can specify other systems to be run before or after the defined system, creating a dependency graph. When the system starts it will check for cyclic dependencies and raise an error if there are some.

With the execution order in place, systems are assigned an ID according to the topological sort defined by the dependency graph, and then run in this order for each stage.

|

|---|

| When the execution order is specified using the dependency graph, systems will have the same execution order in all stages. |

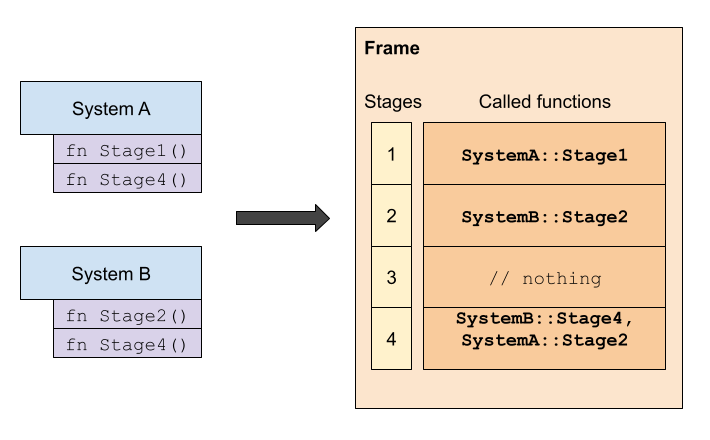

You could also ignore the execution order specification entirely and rely on stages to define execution order. If you want System A to execute some stage before System B, you could request a stage function for B in a stage later than the one used in A. Let’s see an example:

|

|---|

In this example, the code in SystemB::Stage2 will always execute after SystemA::Stage1. Since there’s nothing to run in stage 3, that stage is skipped. Then in Stage 4, we execute both SystemB::Stage4 and SystemA::Stage4 in a non-deterministic order. since there’s no dependency order specified. |

In this example, we want System B to execute something after System A’s Stage 1. We define SystemB::Stage2 to execute such code since we know that Stage 2 always executes after Stage 1. If we define stage functions for both systems for the same stage, the execution order is non-deterministic.

Conclusion

Overall this is the general model we are trying to implement. There are still a lot of unknowns and considerations we might not taken into account yet, but we’re addressing them as they come. We still don’t know how internal engine systems will get along with this design, we don’t know how to easily serialize the state of a game, and so on. In the following articles, I will explain some other features we have implemented, along with the progress of our project!