[proto-ecs] The Render Foundation

Luis Diaz / December 2024 (1491 Words, 9 Minutes)

proto-ecs is a game engine I’m developing with a friend to learn more about engine programming. It’s written in Rust, and the main feature is an entity system that allows trivial parallelism of gameplay code. While that part is well-advanced, we lacked a way to visualize the game!. Narutally, the next step was to build the rendering system, or at least lay its foundation.

You can find more details about proto-ecs here.

As with many game engine enthusiasts, building the render system was one of the most exciting milestones. After countless lines of code, we finally have a basic render system capable of displaying 3D models on screen!

In this article, I’ll share how we structured and implemented the Render API, and how the render thread integrates into proto-ecs’s architecture.

The low-level API design is heavily influenced by this talk from Sebastian Aaltonen and the general render architecture is inspired by this article.

API Structure

For the render API, we aimed for:

- No leaking of platform-specific details into the render code.

- Easy implementation of new rendering APIs, especially for maintainment.

- Good ergonomics for writing rendering code.

- Parallel execution, allowing the simulation to run independently while the renderer draws a frame.

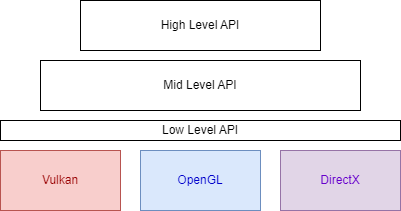

Following Sebastian’s principles, we designed a multi-layered structure:

- Low Level:

-

A thin abstraction over graphics APIs (e.g., OpenGL, Vulkan, Metal).

-

Avoids unnecessary abstraction while preventing platform-specific code from leaking into higher layers.

-

To support a new API, you just have to implement the

RenderAPIBackendtrait. -

Operates with index/vertex buffers and shaders.

-

- Mid Level:

-

Builds on the Low Level layer.

-

Manages models, materials, lights, and cameras.

-

Abstracts rendering details, agnostic of the underlying API.

-

- High Level:

-

User-facing systems like UI rendering, animations, and particles.

-

Not yet implemented, but planned as the next phase.

-

Currently, the engine only supports OpenGL, and we are using Phong Shading with fixed parameters to test this structure (hence the white-purple tint of this model). The next step will be implementing PBR.

Entity system

Integrating rendering into our entity system was surprisingly straightforward using datagroups, local systems, and global systems.

A datagroup is a collection of entity-related data. Similar to Unity components, but without update functions or lifecycle logic. A global system is an object processing multiple entities based on specific datagroups, specified as dependencies.

More about Datagroups, Global Systems, and Local Systems here

We introduced a new global system: RenderGS, and a new datagroup: MeshRenderer.

To display an entity in scene, users add a MeshRenderer datagroup, which requieres a Transform datagroup

to define position, scale and orientation. The MeshRenderer specifies models and materials, while the RenderGS

global system collects scene data (e.g., lights, cameras, models) at the end of each frame to pass to the render thread.

The MeshRenderer allows entities to specify a list of models and materials.

Then the RenderGS global system will run at the end of each frame to collect all information in the scene needed to render a frame and it will send it to the Render Thread.

This information includes lights, cameras, transforms, models, and materials.

We use double buffering, so the render thread will always draw the previous frame,

while the simulation is a frame ahead.

We also use double buffering: the render thread draws the previous frame while the simulation stays a frame ahead.

Render Thread

While the main thread runs the simulation and updates the entity system, the render thread draws the previous frame in parallel. Communication between threads happens via shared memory.

We use a RenderThreadSharedStorage struct to hold all the information shared with the main thread,

separating the memory internally used by the render thread. For now, it looks like this:

pub struct RenderSharedStorage {

last_frame_finished: AtomicBool,

running: AtomicBool,

started: AtomicBool,

/// Description of the next frame.

frame_desc: RwLock<FrameDesc>,

/// Store shaders by name, for easier retrieval

name_to_shaders: RwLock<HashMap<String, ShaderHandle>>,

}

Instead of locking the entire struct, each field can be accessed independently using atomics and RwLock.

It contains some metadata about the current state of the render thread and,

frame_sec, the information required to render a frame.

It’s updated by the main thread before being consumed by the render thread.

Both the main thread and the render thread have a sync point where they operate this data. At the end of each frame, the main thread will lock the frame_desc variable and update the frame description with the information collected from the entity system. Then, when the render thread is finished with the previous frame, it will also lock the frame_desc variable and move its content to its internal memory, to free the lock as soon as possible.

What happens when the main thread already finished a new frame, but the render thread is not finished with the previous one? There are multiple approaches to this problem:

- Skip frame: Replace the undrawn frame with the next frame. This approach is very easy to implement and it makes a bit of sense. It’s already too late to draw the frame in the buffer, so we replace it with a new one. It can cause issues when the render thread slows down because if it happens too many times in a row, the next drawn frame will have a wildly different state to the previous one, causing a bad experience for the user.

- Wait for the render thread to finish: Pause the simulation until the render frame is finished. This approach can cause stutter, but at the least the state won’t change significantly between frames.

There are probably more and more sophisticated approaches to this problem, but for now these are the most direct ones. Currently, we’re using the Skip Frame approach for its simplicity.

Resource lifetime and allocation

A key part of this design is how resources are managed. Usually, the creation of a resource like a shader, a material, or a model would be implemented with RAII: you create a new instance using a constructor, and the destructor would clean up all of its resources when the object is no longer needed. The problem is that the engine programmer would have little control over the control flow of these destructions. And it’s worse if a destructor can cause side effects outside the destroyed object, which is very likely if you use some sort of bookkeeping system. And what if the modified memory is in another thread? Pure chaos!

Let’s take a look at how the FrameDesc struct is defined:

pub struct FrameDesc {

pub render_proxies: Vec<RenderProxy>,

pub camera: Camera,

// Lights not yet implemented :(

}

pub struct RenderProxy {

pub model: ModelHandle,

pub material: MaterialHandle,

pub transform: macaw::Affine3A,

pub position: macaw::Vec3,

}

FrameDescdescribes a frame’s state, by specifying the camera, lights (coming soon), and objects to draw.RenderProxyis a description of an object from the perspective of the render. Since it doesn’t care about entities, the information in this struct is very simple, it’s just the model, material, and transformation of an object.

All macaw types are just structs of floats. The handles are all very similar to the ones described in this post,

just an index and a generation number, both of type u32. This means that

copying a RenderProxy instance is just memcpy, you don’t have to call destructors or move resources.

We can just assign new RenderProxy instances to the array without the overhead!

But if the thing passed are just handles and not the actual object or pointer to the object, then where’s the actual memory located? We decided that all resources related to rendering belong to the render. Once the resources are loaded they are managed by the render, and resource destruction is a request to the render thread, and it will be fulfilled eventually, but not immediately.

The engine will only use the handles and the actual data will be managed by the render thread, which is the primary user of this data anyway.

We still need a better way to handle resource loading, but that will be a matter for another day. For now, we just want to have a foundation system for the render.

Conclusions

Our API design is very simple and useful, allowing us to easily create new render API backends without leaking platform-specific details too high into the abstraction stack. It plays nicely with multi-threading thanks to the heavy use of PODs to send data to the render thread. It’s also very simple to glue to the entity system thanks to our global system design.

There’s still a lot of work to do regarding the render, but this is a nice and simple foundation structure to build upon.